Author Interview: Nancy Kress

Ms. Kress claims she never intended to become a writer but staying at home with two infants gave her time to experiment—and embroidering didn’t work out. Lucky for us! She’s the author of twenty-one books: thirteen novels of science fiction or fantasy, one YA novel, two thrillers, three story collections, and two books on writing. Kress’s short fiction has appeared in all the usual places. She has won three Nebulas: in 1985 for Out of All Them Bright Stars, in 1991 for the novella version of Beggars In Spain, which also won a Hugo, and in 1998 for The Flowers of Aulit Prison. Kress is the monthly Fiction columnist for Writer’s Digest Magazine and teaches regularly at Clarion. She spoke to me about her writing, teaching, and foray into e-publishing from her home in Silver Springs, Maryland.

Ms. Kress claims she never intended to become a writer but staying at home with two infants gave her time to experiment—and embroidering didn’t work out. Lucky for us! She’s the author of twenty-one books: thirteen novels of science fiction or fantasy, one YA novel, two thrillers, three story collections, and two books on writing. Kress’s short fiction has appeared in all the usual places. She has won three Nebulas: in 1985 for Out of All Them Bright Stars, in 1991 for the novella version of Beggars In Spain, which also won a Hugo, and in 1998 for The Flowers of Aulit Prison. Kress is the monthly Fiction columnist for Writer’s Digest Magazine and teaches regularly at Clarion. She spoke to me about her writing, teaching, and foray into e-publishing from her home in Silver Springs, Maryland.

Faith L. Justice: You’ve been selling your stories since 1976. When did you break into full time writing?

Nancy Kress: In 1990 my twenty-hour-a-week job at an advertising agency ballooned to fifty hours. If I could have kept it to twenty hours a week, I probably would have stayed there for several more years, but I wasn’t writing for myself. My boss was my best friend and we argued about this constantly until finally I just said “No!” and quit to become a full time writer. I was already earning as much or more through my fiction as I was with my day job. I was also married, so two incomes made it financially feasible. I don’t recommend people go around quitting their jobs to write full time until they can support themselves. And you have to love it. If you don’t, it’s really a lot of pain. There are writers who hate writing, but I don’t understand them.

FLJ: Three of your awards have been for novellas. What’s the difference writing in the shorter or longer forms?

FLJ: Three of your awards have been for novellas. What’s the difference writing in the shorter or longer forms?

NK: The novella is my preferred length. It’s long enough to develop a science fiction environment but not so long that you need more than one plot line. It usually takes only two weeks, not counting the research. The feel of writing it is different. If I had my druthers that’s what I’d write, but you can’t make a living writing novellas.

A novel takes about nine months. There are the inevitable interruptions and I always get stuck in the middle. For me a novel goes very fast in the beginning, the end goes fast, and the middle is hell. Although I like that point about 3/4 of the way through when it all comes together—all those strands you’ve so laboriously laid down: the science, the setting, the character, the plot—all seem to gel.

Short stories take about a week. I write the stories I want and send them out—usually to Gardner [Dubois of Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine] first—and see who buys. I get asked to do theme anthologies occasionally. “Steamship Soldier” just lost the Hugo.

FLJ: Where do you start—the science, setting, character?

NK: I begin with a strong sense of character. I can’t start until the major character falls in line. The plot possibilities flow out of the interaction of that character and whatever science fiction situation I set up.

FLJ: You’re known for your meticulous research in both your science fiction and suspense. How do you go about that?

NK: I used to do it when I needed it, but now I do more before I start. Science is becoming more and more complex. If it’s physics, I go to Charles. I read science journals written for the lay person—Scientific American, the front half of Science. Frequently, I’ll be alerted by something in the newspaper and then I’ll follow up in the journals. I use the web to research institutions like the FBI and CDC. There’s a lot of official information available. To get a personal view for my thrillers, I read books by people who left the FBI.

FLJ: What about your writing process—do you have an office, work on a schedule?

NK: I have a smallish room—about 10 x 12—that was made into a study for me. That’s its sole purpose. It has a desk, bookshelves, laptop, and a couch for sitting around pondering things. Basically I’m a morning person so I try to write from 8:30 until 1 or 2, but it doesn’t always work out, especially around the holidays. In the afternoons, I do less creative work—student manuscripts, galleys, research, business letters. When the children were small I adapted to their schedule. When I worked for an ad agency, I wrote for them in the morning and myself in the afternoon. The key thing for any writer is to find a regular time to write and just do it. That’s the only way you can learn. Writing is such a lonely business. It’s yourself and a bunch of people, who don’t exist, occupying that 10 x 12 room day after day. Being married to another writer helps, but it also helps to get out on a regular basis—to cons and to teach.

FLJ: You married Charles Sheffield three years ago, what’s it like living with another writer?

NK: It’s interesting. We read each other’s work and critique each other’s manuscripts. As I move more heavily into hard science fiction, Charles is a tremendous resource for me in terms of science—especially physics. But it’s hard to maintain a balance. I moved from Rochester [New York] to Silver Springs. We built an extension on the house to take care of my stuff. My kids moved out and one of his daughters moved in. Things change all the time and I have to constantly readjust.

FLJ: You also write a regular column for Writer’s Digest Magazine. How does that work?

FLJ: You also write a regular column for Writer’s Digest Magazine. How does that work?

NK: The topic always comes first. I think of something from my own work, a class, or something a student is having trouble with or did well. Then I think about what I know and start looking for examples of how it’s been done right in professional novels. I’m surprised at how many different topics there are. I’ve gone five years without repeating. I didn’t expect that much variety.

The columns are only about 1500—1800 words and the deadline is regular. One interviewer described my non-fiction style as short, punchy, like talking to someone over the kitchen table. I guess that’s because there are no characters to hide behind.

FLJ: How do you organize your books on writing?

NK: When it’s time to do a book, I go through the columns, choose the ones that go together in some coherent thread, modify them and stitch them together. The columns come first.

FLJ: You’ve crossed genres a couple of times moving from fantasy to science fiction to suspense and back. How has that worked?

FLJ: You’ve crossed genres a couple of times moving from fantasy to science fiction to suspense and back. How has that worked?

NK: The switch from fantasy to science fiction was easy. I was ready for it and interested in it. Since fantasy books weren’t selling well anyway, it worked. The switch from science fiction to suspense was a disaster. I got good reviews, especially for Stinger, but people couldn’t find my books. Because of my name, they were shelved with the science fiction. My science fiction fans didn’t want to read suspense and the thriller readers couldn’t find them. It’s a shame publishing is so into categorizing. The thrillers are my personal favorites among my books. Sometimes the problem children are the favorites.

FLJ: How do you market yourself and your work?

NK: Not as well as I should. When my thrillers—which are set in Washington, D.C.—came out I should have sent copies to the local newspapers, radio and TV, gotten myself down there, alerted the bookstores and arranged for signings. I didn’t do any of that. I know I should have, but I don’t like it and it’s really time consuming. So I market at conventions, which I really enjoy. You can pick up a lot of readers at a big con. They see you on panels and get interested.

FLJ: How do you see new technology—print on demand, eBooks, web marketing—influencing the publishing industry?

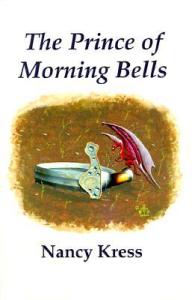

NK: I think we’re all waiting to see. My first book The Prince of Morning Bells is back in print as a print-on-demand book at Fox Acre Press and several of my short stories and novellas are available at Fictionwise.com. That seems to be working well. If something is out of print anyway, there’s nothing to lose. For new manuscripts, many of us are sticking to the older roots until we see what happens. As usual, the mavericks and pioneers are out there experimenting. We’ll find out how they make money.

NK: I think we’re all waiting to see. My first book The Prince of Morning Bells is back in print as a print-on-demand book at Fox Acre Press and several of my short stories and novellas are available at Fictionwise.com. That seems to be working well. If something is out of print anyway, there’s nothing to lose. For new manuscripts, many of us are sticking to the older roots until we see what happens. As usual, the mavericks and pioneers are out there experimenting. We’ll find out how they make money.

FLJ: You teach writing regularly. What advice do you give beginning writers?

NK: Books and courses can be shortcuts, but eventually you just have to write and be willing to rewrite. I suggest starting with short stories. You can learn the basics—character, structure, language, science fiction plausibility—without investing so much time. A lot of students are very wordy, they prose on and on. Try to find a time to write on a regular schedule and just do it. And remember, the first draft should not be considered carved in stone.

You also need to read—both the science fiction magazines and the classics from the last fifty years. Many students introduce a sparkling idea that was old in the 1960’s and wonder why their stories don’t sell. You need to know what’s been done in the field and in science and how to put them together in an interesting way.

FLJ: What are the books that everyone should read?

NK: Representative styles and classics: Ursula K. Le Guin’s Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed; Arthur Clarke’s Childhood’s End; space opera like Ringworld by Larry Nivens; something cyber-punk like Gibson’s Necromancer. Holy Fire by Bruce Sterling is a favorite of mine. Lois McMaster Bujold writes popular stories—any of her Miles Vorkosigan Saga. Read at least one of the strong feminist writers. I like Sheri Tepper’s Grass. Mary Doria Russell’s The Sparrow has made a big splash in the literary realm. Read something by Greg Bear – Forge of God or Blood Music—or Gregory Benford’s Timescape to see how science can be made interesting. And don’t forget the magazines: Analog Science Fiction, Asimov’s Science Fiction and Locus Magazine.

FLJ: Do you recommend taking classes?

NK: Classes can help, but it depends on the instructor. Taking a writing course from someone who doesn’t know or understand science fiction can be worse than taking no course. Look for a working professional who is sympathetic to a wide variety of subgenres. Find out what they’ve written and what the structure of the course will be. Everybody should critique your work. The teacher can give you a professional view and the others give you a reader’s view—and you’re ultimately writing for readers.

FLJ: How can students evaluate the teacher/course before taking it?

NK: It can be difficult. First of all find out what they’ve written. You can call the teacher and find out what the structure will be. Most places won’t give you the teacher’s number, but will take yours and ask the teacher to call you at her convenience. Sometimes you have to do this four or five times before the teacher feels guilty enough to do it. Ask what the structure will be, are there any subgenres you don’t feel comfortable with, that sort of thing. Most people don’t resent it if you keep it fairly short and not critical.

If you want to be a professional, check out Clarion East or West. They only take about a third of all students that apply. These people take six weeks out of their lives and that’s not easy for most adults to do. Also at Clarion, we look at things in more depth, because we have more time. We’re probably a lot harsher on manuscripts, but the students expect that because Clarion is known as the boot camp of science fiction.

© 2008 by Faith L. Justice

Author’s Note: Ms. Kress has published numerous novels, novellas, and short stories since our interview in 1999. She also lost her husband Charles Sheffield to brain cancer in 2002 and moved back to Rochester, New York. In 2011 she married writer Jack Skillingstead.They currently live in Seattle, Washington. Portions of the interview have appeared as:

- “The Unintentional Writer: An Interview with Nancy Kress” in Inscriptions Magazine and Fears Magazine, 2001

- “Nancy Kress: Writer and Teacher” in com, 2001

- “Nancy Kress on the Nuts and Bolts of Science Fiction” in com, 2000