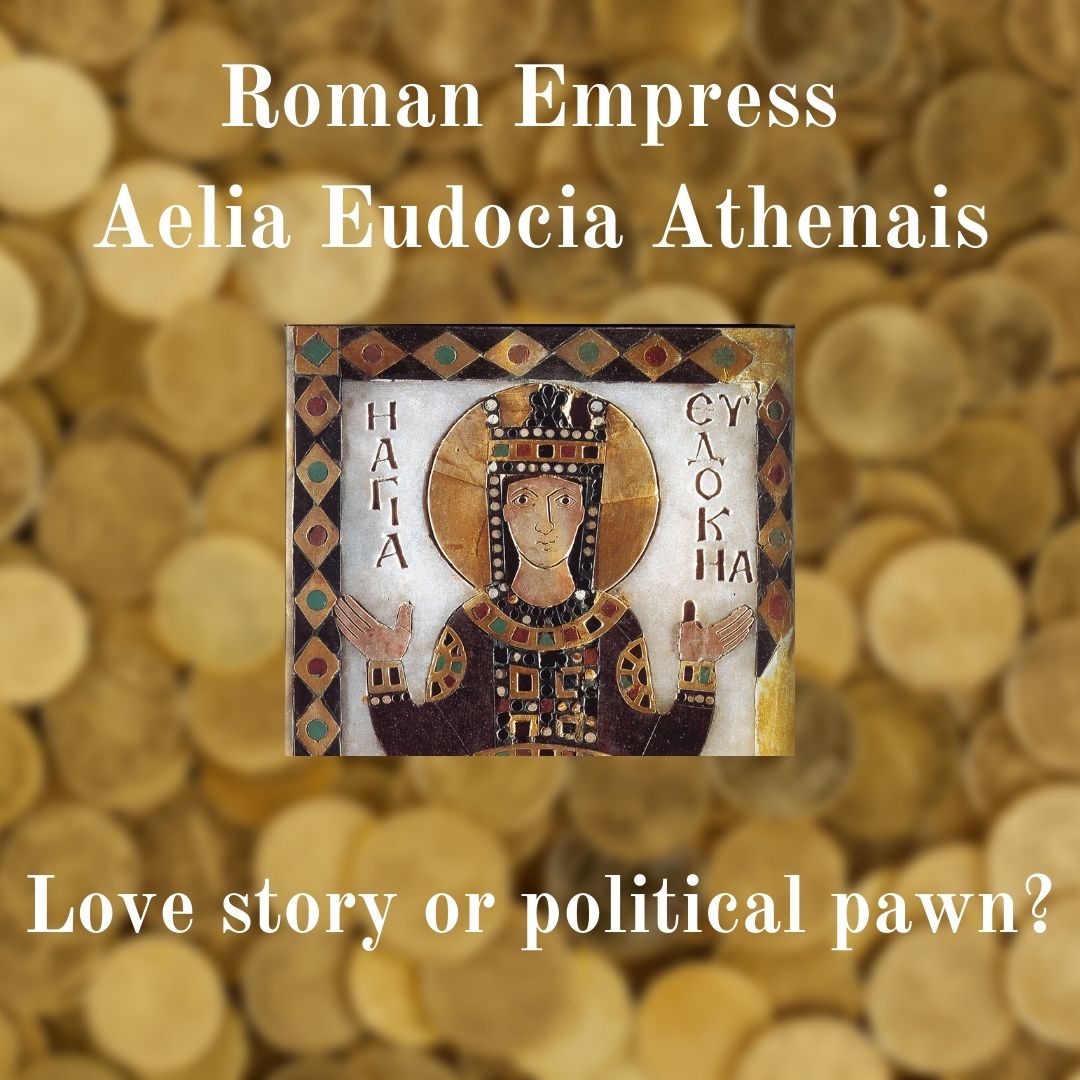

Roman Empress Aelia Eudocia (Athenais)

Love story or political pawn?

(b. 400/1, d. 460, Empress 421-460)

Empress Aelia Eudocia married Empress Pulcheria’s brother Theodosius II. She was born Athenais, the only daughter of a pagan Greek philosopher named Leontius who taught at the Academy in Athens. He educated his daughter and she later became known for her poetry and literature, some of which survives today. Athenais is also the protagonist in my work in progress—the third book in the Theodosian Women series. How did a beautiful, but poor, pagan girl attract the attention of the Most Christian Emperor Theodosius II?

The fanciful love story some ancient historians (writing a hundred years after the fact) tell goes like this: When Leontius died, he left his fortune to his sons Gessius and Valerius leaving only one hundred coins to Athenais because “her good fortune, surpassing that of all other women, will be enough.” (The assumption being that “good fortune” in this phrase refers to her beauty.) She asked her brothers to share, but they refused.

Athenais then went to Constantinople to live with an aunt and uncle and take her case to a higher magistrate. Supposedly, Empress Pulcheria observed Athenais make her case and was impressed, not only with the girl’s beauty, but her brains and elocution. Since she was on the lookout for a suitable wife for her brother she brought Athenais to his attention and it was love at first sight.

Athenais was baptized and took the Christian name Aelia Eudocia in tribute to Theodosius’ mother. (An aside: She used her Christian name only on formal occasions. She preferred Athenais among her family and intimate associates. I use Athenais to break up the Eudoxia/Eudocia confusing line of names.) In the love story, her wicked brothers fled after hearing she was marrying the Emperor, thinking Athenais would punish them. She recalled them and showered them with honors, showing her Christian charity and forgiveness for their sins. And everyone lived happily ever after—a romantic rags to riches story with moral themes to suit the times.

Kenneth G. Holum in his Theodosian Empresses: Women and Imperial Dominion in Late Antiquity tells a more probable story. The Hellene faction, including Theodosius’ boyhood friend Paulinus, were likely behind finding a more secular bride to counter Pulcheria’s strict religious influence at court. Pulcheria certainly wouldn’t want a sister-in-law who came with a raft of male relatives that could rival her own influence with her brother or even challenge him for the throne. Valerius, Gessius, and the uncle were given high offices and honors just before the wedding and for years after.

The previously pagan Athenais and saintly Pulcheria continued to clash over myriad political policies and church doctrine, but primarily over the big prize: influence over Theodosius. The fact that Athenais could produce a son gave her a leg up on Pulcheria until it became clear that no male heir was forthcoming. Athenais gave birth to one child who survived into adulthood, a daughter Licinia Eudoxia. A second daughter Flacilla died in childhood, and a son Arcadius was still born or died in early infancy snuffing Athenais’ fertility as a source of power.

But Athenais was smart as well as pretty. She learned the ins and outs of court politics and learned to wield her own sources of power which shifted over the years. How she did that and her fate at court is the subject of my next book. Watch for it!

Coming next: Empress Justa Grata Honoria, Placidia’s wayward daughter.

Image of mosaic showing Empress Aelia Eudocia (Athenais) licensed as Creative Commons By Elena Chochkova – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4485258