Burning Books: What Really Happened to the Great Library of Alexandria

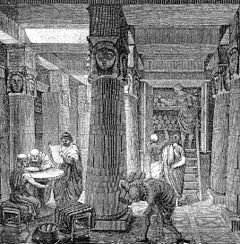

The Great Library of Alexandria conjures images of bearded scholars strolling marble halls, studying rolls of papyri at large wooden tables, or arguing with colleagues under covered walkways. The loss of “the world’s knowledge” through wanton destruction is a metaphor for the coming of the Dark Ages in Europe. But what was the Great Library really and how was it destroyed?

A Little History

After Alexander the Great’s death in 323 BC, his general Ptolemy Soter I took over the province of Egypt and his descendants ruled until the death of Cleopatra in 30 BC. Ptolemy was advised by a former Athenian named Demetrius to “collect together books on kingship and the exercise of power, and to read them” so as to become more like Plato’s ideal philosopher-king. Ptolemy then sent a letter to his fellow rulers throughout the classical world asking that they send him works of authors of all kinds because he wished to collect “the books of all the peoples of the world.” This was the beginning of the Royal Library which eventually became the Great Library.

Ptolemy and his son Ptolemy II Philadelphus constructed a walled palace district taking up almost a third of Alexandria which not only housed the royal residences, but also a sprawling temple to the muses—the Museum which included the Royal Library, scholars’ living quarters, classrooms, a zoo and gardens with exotic plants. Strabo, the first century B.C. geographer, described it:

“The Museum, too is part of the royal palace. It comprises the covered walk, the exedra or portico, and a great hall in which the learned members of the Museum take their meals in common. Money, too, is held in common in this community; they also have a priest who is head of the Museum, formerly appointed by the sovereigns and now appointed by Augustus.”

Strabo didn’t describe the library because it wasn’t a separate building. Scrolls were kept on shelves under the covered walkway and in specially built niches throughout the Museum. The Museum and Library became one of the great learning centers of antiquity and attracted scholars from all over the world to study philosophy, mathematics, science, nature, literature, and medicine. The library collection continued to grow with some estimates that over 500,000 books were collected through purchase or confiscation. The collection became so large, that “daughter” libraries were formed outside the Museum. The best known was at the temple of Serapis in the Rakhotis district. These were open to the public.

Who Burned the Great Library?

So how did the Great Library go up in flames? Some blame Julius Caesar. When he was besieged in the palace district in 48 BC, he started a fire among ships in the harbor which spread to warehouses on shore. Livy wrote that “by chance, at the time of the fire some 40,000 book scrolls of excellent quality were burned in a harbor warehouse.” Since they were in warehouses, these books were probably luxury trade goods, not part of the library which was safe behind walls which the fire didn’t reach.

Almost three centuries later Queen Zenobia of Palmyra broke away from the Empire and briefly conquered Egypt and Alexandria in AD 269. Emperor Aurelian besieged Alexandria four years later and inflicted significant damage to the palace district. In 298, Emperor Diocletian completely destroyed the palace district while putting down an uprising. These acts of war no doubt did significant damage to the collection, but probably didn’t totally destroy it (think of the bravery of the Iraqi Museum workers who managed to salvage many of their most precious items from the looting after Baghdad fell.) The Museum and its library lived on, probably in a much reduced state.

In 365, a devastating tsunami–the result of a magnitude 8 earthquake–hit Alexandria killing over 5,000 people and destroying over 50,000 homes. The palace district subsided into the sea. Archaeologists discovered the remains in the harbor in 1995. What was left of the museum and library continued on in and around the district known as Caesarium. Recent archaeology in that area has revealed an extensive system of lecture halls. As late as 415, we have sources referring to the Museum when Hypatia, the famous mathematician and Lady Philosopher of Alexandria was murdered.

Bishop Theophilus is often accused of destroying the Great Library when he razed the pagan Serapeum in 391 and built a Christian church on its ruins. At one point there had been a public library at the Serapeum, but Rufinus doesn’t mention it in his description of the temple complex shortly before it’s destruction. So it’s likely that library had also dwindled or disappeared before 391. If any books were destroyed, they were part of the “daughter library” not the “Great Library.”

The last culprits accused of destroying the “Great Library” and bringing on the Dark Ages were the Arabs who invaded and took over Alexandria in 641. By that time, what was left of the Great Library had probably dwindled substantially, due to neglect–bugs, theft, and deterioration–to a much smaller collection of mostly Christian texts. There’s an apocryphal story that says the General Amrou wrote to his Caliph Omar asking what to do with the remains of the library and received this reply:

“If their content is in accordance with the book of Allah, we may do without them, for in that case the book of Allah more than suffices. If, on the other hand, they contain matter not in accordance with the book of Allah, there can be no need to preserve them. Proceed, then and destroy them.”

Supposedly, the books were distributed to the public baths to feed the fires that warmed the water. Ibn al-Kifti wrote, “They say that it took six months to burn all that mass of material.” But we don’t know who “they” are and what motives they might have for spreading such a story. Their are no written eye-witness accounts or archaeological evidence for or against this theory.

In Conclusion

Paper (papyri, vellum) is a fragile medium and books are subject to fire, water, insects, thefts, and copy errors. There were several spectacular assaults on the physical library which contributed to it’s decline, but there doesn’t seem to be any one culprit. It’s not surprising that so little has come down to us from ancient times. We should be careful who and what we blame for the “Dark Ages” (which many medieval scholars would dispute were not that dark) and remember that what has survived did so because it was preserved by Christian monks and Muslim scholars.

For nearly a thousand years, the Great Library waxed and waned in Alexandria, serving scholars and the public alike. In October 2002, the newest incarnation was inaugurated: the Bibliotheca Alexandrina. In 1974, the Egyptian government embarked on an ambitious project to recoup the glory of the Great Library. The new one has shelf space for eight million books; houses three museums, four art galleries, a planetarium and a manuscript restoration lab in a gray Aswan granite building that looks like a tilted sundial (see picture.) Like the original, the collections at the Bibliotheca Alexandrina are donated from all over the world.

For nearly a thousand years, the Great Library waxed and waned in Alexandria, serving scholars and the public alike. In October 2002, the newest incarnation was inaugurated: the Bibliotheca Alexandrina. In 1974, the Egyptian government embarked on an ambitious project to recoup the glory of the Great Library. The new one has shelf space for eight million books; houses three museums, four art galleries, a planetarium and a manuscript restoration lab in a gray Aswan granite building that looks like a tilted sundial (see picture.) Like the original, the collections at the Bibliotheca Alexandrina are donated from all over the world.

Selected sources:

- The Vanished Library: a Wonder of the Ancient World by Luciano Canfora (University of California Press, Berkeley, CA, 1990)

- Bibliotheca Alexandrina Official Web Page

- “The Burning of the Library of Alexandria” by Chester Preston

I am going to get addicted to this blog. I love it!

I just feel smarter reading this saga… fascinating! I am an ardent fan!

Thanks, Jean and Laurence! I hope to keep up the good work.

My God, such an extensive article. Thank you so much! I am so sad to learn the vast amount of knowledgelost… (six month to burn, OMG!), but I hope we’ve learned to do the better now…

“remember that what has survived did so because it was preserved by Christian monks and Muslim scholars.”

Let’s not forget the Byzantines, who never lost it.

The mistake we moderns often make is to suppose that if one library is lost, there were no others. Alexandria continued to be a center of philosophy and “science” down to the eve of the Arab invasion. John Philoponus has fair claim to being the first of the real scientists, given that he carried out experiments.

+ + +

The 500,000 figure is totally unrealistic when you compute the shelvage that would have been needed and the size of the building.

+ + +

Copying a scroll was a laborious thing and copyists would have had to make judgments of which ones to copy and which to let go. E.g., We have Strabo’s Geography; but not Eratosthenes earlier Geography for the simple reason that no one wanted to recopy an out-of-date book.

Very interesting that even the Great Library had it’s local “branches”. ;o)