Author Interview: Ursula K. Le Guin

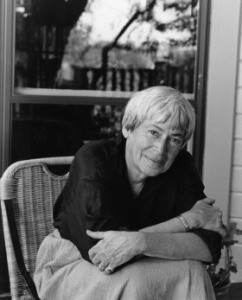

Before J. K. Rowling and Harry Potter, there was Ursula K. Le Guin and her best-selling children’s stories of wizards and magic in Books of Earthsea. Before Star Wars there was Le Guin’s award-winning science fiction classic The Left Hand of Darkness. Born in 1929 to an anthropologist father and writer mother, Le Guin submitted her first story at the tender age of twelve. It was rejected. But she persevered and has defied categorization by publishing mainstream stories, novels, children’s books, essays, literary criticism and poetry. She’s accumulated more awards than can reasonably be listed: the National Book Award, five Hugos, five Nebulas, the Kafka Award, a Pushcart Prize and the Howard Vursell Award, among many. Ms. Le Guin talked to me from her home in Portland Oregon about her art, science fiction, and newest book.

Before J. K. Rowling and Harry Potter, there was Ursula K. Le Guin and her best-selling children’s stories of wizards and magic in Books of Earthsea. Before Star Wars there was Le Guin’s award-winning science fiction classic The Left Hand of Darkness. Born in 1929 to an anthropologist father and writer mother, Le Guin submitted her first story at the tender age of twelve. It was rejected. But she persevered and has defied categorization by publishing mainstream stories, novels, children’s books, essays, literary criticism and poetry. She’s accumulated more awards than can reasonably be listed: the National Book Award, five Hugos, five Nebulas, the Kafka Award, a Pushcart Prize and the Howard Vursell Award, among many. Ms. Le Guin talked to me from her home in Portland Oregon about her art, science fiction, and newest book.

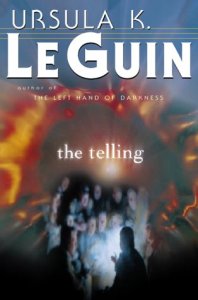

Faith L. Justice: This is your first novel (the telling) in ten years. Why the gap?

Faith L. Justice: This is your first novel (the telling) in ten years. Why the gap?

Ursula K. Le Guin: I have no idea. I have no control over my writing. I have lots of good intentions, but no control. I seemed to be writing stories and novellas. I love novellas, but I was getting sort of lonesome for a novel. When I got this one started, I thought it would be a novella, but it wanted to be a novel. I’m working on another novel now.

FLJ: Is it going to be another Hainish novel?

UKLG: Another Earthsea. That taught me never to say never. I thought I had come to the end of that story. That’s what I mean by no control.

FLJ: You’ve described yourself frequently as an artist. What does that mean to you?

ULKG: There are dance artists, painting artists, writing artists. Authors are writing artists. I think people restrict the term artist to mean painters and sculptors. I think the practice of art, in whatever medium you do it in, is one large similar thing. I’m just glad that words are my medium, because I love them.

FLJ: So you consider it something of a sacred calling?

ULKG: It’s probably not a term that I would originate, but yes I do. Any craft pursued with real seriousness has a sacred quality about it, unless you’re just doing it for the money. That’s rather rare. Most people do it, at least partly, for their own sake. This is true of teaching or carpentry, not just the fine arts.

FLJ: Many social influences have been attributed to your work—your parents (anthropologist & author), their work with Native Americans, feminism. What are your literary influences?

UKLG: Oh God! Practically everybody that ever wrote a novel that I read…and a lot of poets too. I always read everything. What I like is a good book. It doesn’t matter whether it’s fantasy or science fiction or War and Peace. If it’s good, it’s good. If it’s not, it’s not. When I’m cornered, I say one of the long term major influences on my work is Virginia Woolf. She has a lot of stuff that’s incredibly fruitful for me.

FLJ: What makes a good book?

UKLG: Magic. Things move, things change, you’re changed at the end of it as a reader. You’ve been taken somewhere and shown something.

FLJ: Many people say they’ve been changed after reading one of your books.

UKLG: I’ve been told by teenagers that I got them through a bad year. Boy, it makes you feel fairly humble and it’s a little scary, because you do realize you influence people when you tell a story. You have to take serious the fact that you may change a life.

FLJ: Does that affect you when you’re writing?

UKLG: Not exactly. Actually, nothing affects me when I’m writing. I’m just trying to do the story. Outward considerations aren’t there. There’s a kind of ethical question when you’re writing for kids. You have to stand back from the work and say “Could this scare an eight-year-old? Could it do any harm?” The editors don’t do that for you. With children’s literature, the writer has to be in the foreground. There’s a cruel streak to Roald Dahl. One of my daughters was very fond of his earlier books. I was very happy when she outgrew him, I have to say. There’s something a little gross and a little cruel in his work. Some of the books, like the Goosebumps books, look sort of gross or dumb, but they’re harmless. I think kids need a lot of dumb stuff. Roughage in the diet.

FLJ: You’ve occasionally been critical of the academic influence on literature calling it “stifling.” What’s the problem?

UKLG: The labeling. Goodness, I grew up academic. My husband’s a professor and I’ve taught. I love good literary criticism and I appreciate it. But there’s this queer thing in academia that says realism is the only literary fiction and all other kinds of fiction are sub-literary. That’s just crazy. That knocks out about nine-tenths of all American literature. Once the first South American came up with magical realism, you couldn’t say that only realism is literary. The magical realists were a great help to people like me. They broke down some of those arbitrary walls and categories.

FLJ: You’ve said that science fiction as literature allows us to think through dreadful results; more importantly, allows us to think of alternatives.

UKLG: There are different ways of thinking, being and doing things. Both science fiction and fantasy offer more options. They let you think through an alternative without actually having to do it. I think one of the functions of all fiction is to let you live other lives and see what they’re like. It widens the soul. In science fiction and fantasy there’s an attitude of “we don’t have to do it this way!” It opens some doors that have been shut.

I have to admit to a certain amount of calculation. If you look at my books, you’ll find that very few of the central characters are white; they’re mostly people of color. You don’t notice it particularly and you don’t see it on the cover. The publishers refuse to put people of color on book jackets, because they don’t sell. But I’ve always done that deliberately because most people aren’t white. Why in the future would we assume that they would be? My assumption is we’ll all turn out sort of café au lait colored. Look at Tiger Woods; that’s the way we’re going. This is the great thing about fiction; you can get inside somebody else’s skin. If it’s a different colored skin, that’s just more exciting.

FLJ: How do you “give back” to the artistic/writing community?

UKLG: I give classes. I teach at Portland State University in their writing programs. Last spring I did a whole semester at Santa Fe as a guest professor. I usually do one or two workshops in summer; and some others I’m moved to give. “Flight of the Mind” is my most regular workshop. It’s for women and a very good one.

UKLG: I always teach short story. When I have more than a week to do it, I teach a course called “The First Chapter of Your Novel.” It’s very hard to teach writing a novel. There’s too much for the other people in the class to read, but if you work on the first chapter it’s very interesting. These classes are really workshops with a peer group. I facilitate. Advice is absolutely specific to the story.

FLJ: Do you have any advice for writers?

UKLG: To read and to write. Some writers have to be told to write. They don’t know that you can’t be a writer without writing. That’s your job. Some really don’t realize that. They think their job is to meet agents and have experience. They think you can just be rich and famous. Their job is to write. And you can’t write unless you read. If they want to write science fiction they should read science fiction.

FLJ: What kind? What authors?

UKLG: There’re so many kinds of science fiction. Just read around and find the people you like. Some people want to write cyberpunk, others more literary.

FLJ: What do you think will be the influence of new technology—the web/eBooks/books on demand?

UKLG: The publishers are behaving like ostriches, shoving their heads deep in the sand. There’s been a lot of panic and misunderstanding on the part of publishers. They’re trying to grab rights from authors for technologies that haven’t even been invented yet. I don’t know what we’re going to do about copyrights; how to replace it with some other arrangement so we can keep our artists, writers, composers, musicians in peanut butter. It’s very nice for everybody to say literature is going to be free, but we’ve got to feed the people who make it.

The whole idea of everything being available electronically, so you don’t even have to go down to the library, isn’t going to hurt reading. This is wonderful for readers. They talk about reading being replaced, that there will be other things to do. There are already things like television and so on, but people are always going to like to read. It’s a different relationship to the story than film or whatever. My take on this whole technology – especially in regard to reading books – is that it’s very exciting.

I wish it had come along when I was a little bit younger. I’m one of those people who can’t program their VCR. I love my computer, but I don’t know how deep I want to get into the web. I don’t know if I’ve got time. As you get older you realize you have less energy and the days don’t seem to have quite as many hours, so I go on writing. At this point, I’m not plugged in. Lord, I have to answer enough letters as it is!

FLJ: Email might overwhelm you?

UKLG: I’m really afraid it would. Once you get in, you can’t hide. What’s the point of being there if you’re going to lurk and do nothing else. So at this point, I don’t have a modem. We would have to get a second phone line. I don’t know, maybe I’m just too lazy.

FLJ: In your Hainish canon you keep returning to the theme of utopia, especially utopia in the eye of the beholder) What fascinates you about that theme?

UKLG: They don’t work all that well. They’re all populated by human beings. It’s not really a utopia. I wrote about utopias in Always Coming Home. But again, they’re imperfect because the people in them are just people. People aren’t going to be all good. There’s an impulse in a lot of science fiction…if you see the world as it is, and there are a lot of people who are unhappy, what would it be like to alleviate some of that? What I was doing partly with Always Coming Home was make a world that was a little less cruel and hard on people than our world is.

UKLG: They don’t work all that well. They’re all populated by human beings. It’s not really a utopia. I wrote about utopias in Always Coming Home. But again, they’re imperfect because the people in them are just people. People aren’t going to be all good. There’s an impulse in a lot of science fiction…if you see the world as it is, and there are a lot of people who are unhappy, what would it be like to alleviate some of that? What I was doing partly with Always Coming Home was make a world that was a little less cruel and hard on people than our world is.

We’re not a very happy species. We want to grow and develop and be free to be what we want to be. But we’d screw that up, just the way we always screw it up. But, it’s fun to think about. I think readers appreciate being given the room for the mind to move around in. They’re not always attracted to things the way they are. That’s what we have imaginations for. We like to look off into the other rooms.

FLJ: Someone once said that since all these worlds were seeded by Hain, there is no true alien intelligence and these stories are more analogous to bringing together nations and cultures on earth. Are these stories (in part) a collection of political fables?

UKLG: Political is narrowing it way too much. They are certainly human stories even when the sexuality is different as in The Left Hand of Darkness. They are not about aliens. I’m using the other worlds and the other races as metaphors. All I know how to write about are people and animals. There are a lot of animals in my works too and trees. Still nothing that is alien.

UKLG: Political is narrowing it way too much. They are certainly human stories even when the sexuality is different as in The Left Hand of Darkness. They are not about aliens. I’m using the other worlds and the other races as metaphors. All I know how to write about are people and animals. There are a lot of animals in my works too and trees. Still nothing that is alien.

FLJ: You’re straightforward in stating the telling is a reflection of today’s society. For you, what is this story about?

UKLG: That’s the question I always dread. I know why I wanted to write about this. I discovered something shocking to me. In China, they had been practicing something like Taoism—a very popular religion between 2-3000 years-old. It apparently had been nearly wiped out in twenty years under Mao. This was an enormous fact to try to stretch your imagination around. I didn’t know anything much about Taoism as a religion. I translated Lao Tzu and I’ve loved the ideas of Taoism all my life, but the religion is quite different. It’s a series of rituals and traditions and superstitions; very complicated, very popular, very ancient. All this was seen as a big threat to communism and got wiped out or suppressed. It survives only in Taiwan and a few little exile colonies in North America.

This haunted my imagination and I thought “I’ve got to write something about this, but I can’t write this about China, I don’t know anything about China.” I had to put it in metaphorical terms. I had to invent a world where there had been an old popular religion (which had very little to do with Taoism) and suddenly a new political regime comes in and sees this as a big enemy to progress and tries to stamp it out. In this, I drop an observer from another kind of world where religion is dominant to the point of being stifling. I have all kinds of currents and counter-currents.

It was a very hard book to write. I was involved with it in complicated ways and the subject troubled me. It was a real bear. I was playing with things that sort of scare me about our world. This is why I think writing is such a mysterious thing. It wouldn’t go right until I got the central character right—Sutty. I didn’t know who she was for a long time. I started in and it went wrong. When Sutty suddenly came to me and found her voice, then I could tell the story. That’s the kind of thing I just don’t understand. What does it mean when you find the character’s voice? But I had to see it through her eyes and when she came, I was ok.

FLJ: the telling is not only the title, but an artifact in the book and a theme throughout the story. Could you explain what “the telling” is and where it came from?

UKLG: I don’t know where it comes from. It’s a story about telling stories and the importance of getting the story right; to get the story to approximate the truth whatever the truth may be. Yet we have no way to approach truth, apparently, except to tell stories about it and there probably is no final correct version of anything. Like family myths. I found out that I and my three brothers have quite different versions of things we thought we all knew that happened in our lifetime. It’s very interesting to compare the versions and, as you say, they all come down to the same kind of center. The reason they are important is the same, but the versions are so different. Like that telephone game we used to play at parties. This is all very interesting to write about.

FLJ: I thought Sutty, in her journey to learn the telling, felt she had gotten just bits and pieces; but the whole was unknowable by one person.

UKLG: That’s true. The telling is a community of people over a whole world and time—there is no end to it. The point is that everybody shares it, then it keeps going on.

FLJ: At the end of the book the telling is broken.

UKLG: What I was saying is they don’t know how to tell that story yet. They’re scared out of it, they turn away from it. Because they’ve been driven underground, it’s easy to turn their backs to it. They aren’t going to get back into good health until they can tell the story of what’s happened to them.

FLJ: There are also tellers who’ve gone bad.

UKLG: Right, when a religion gets exploitive, the priests make themselves fat cats and the religion gets shaken to its foundation. This is what happens when a religion becomes an institution—dreadful corruption enters it.

FLJ: With one exception this story is devoid of any supernaturalism or magic. When Sutty encounters the “unbelievable” —a seemingly crazy man steps up onto seemingly thin air—she dismisses her observations. What were you trying to accomplish with that scene?

UKLG: That piece just had to be in the book. A good friend of mine who read the manuscript told me to take it out, because it didn’t fit. But it needed to be there. Maybe I’m fudging a bit, but this happened to Sutty and had to be in the book.

FLJ: Thank you for your patience and candor. Where are you off to next?

UKLG: Those killer book tours! Harcourt has certainly been kind to me. I’m going to go up and down the West coast and New York and Harbor Front in Toronto. The rest of it I’m doing like this [by phone], which I think is wonderful. And God bless the web! You can get to a lot of people with a fresh and new interview. Maybe there are just too many authors reading too many books.

© 2008 by Faith L. Justice

Author’s note: I had the distinct pleasure of interviewing Ms. Le Guin twice in 2000. She remained prolific and continued to pour out wonderful novels, short stories and poems until her death January 22, 2018. In 2008 she branched out to historical fiction with her novel Lavina, exploring Bronze Age Italy using the Aeneid as her background. The National Book Awards honored her with the 2014 Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters. Portions of these interviews appeared in:

Author’s note: I had the distinct pleasure of interviewing Ms. Le Guin twice in 2000. She remained prolific and continued to pour out wonderful novels, short stories and poems until her death January 22, 2018. In 2008 she branched out to historical fiction with her novel Lavina, exploring Bronze Age Italy using the Aeneid as her background. The National Book Awards honored her with the 2014 Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters. Portions of these interviews appeared in:

- “A Brilliant Career: Ursula K. Le Guin” in Slate.com, 2001

- “Understanding Ursula K. Le Guin” in Writer’s Digest Magazine, 2001 (cover article)

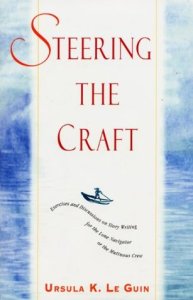

- “Ursula K. Le Guin Steers Her Craft” in Writing-World.com, 2001

- “An Interview with Ursula K. Le Guin” in Space & Time Magazine, 2001

- “The Return of Ursula Le Guin: Le Guin Discusses Her New Novel, the telling” in iUniverse.com, 9/2000

1