Busting Gladiator Myths

Before I researched my novel, Sword of the Gladiatrix, I got most of my ideas and impressions of gladiators from the media: Russell Crowe in Gladiator and (for those of us of a certain age) Kirk Douglas in Spartacus. More recently Starz had a fantastic (in more ways than one) show that ran for three seasons titled Spartacus: War of the Damned. All of these shows perpetuate some gladiator myths that I hope to bust wide open in this post. They also got a couple of things right, which I’ll point out.

Myth #1:

All gladiators were men.

Most were, but not all. Here I’ll give Gladiator a weak thumbs up—they had women in chariots fighting against a group of men in a re-enactment of a classic battle in an arena scene, but other than that, women gladiators don’t show up in most visual media. It’s left to us lowly writers to correct the balance. If you look closely, women in the arena show up in art, literature, and law.

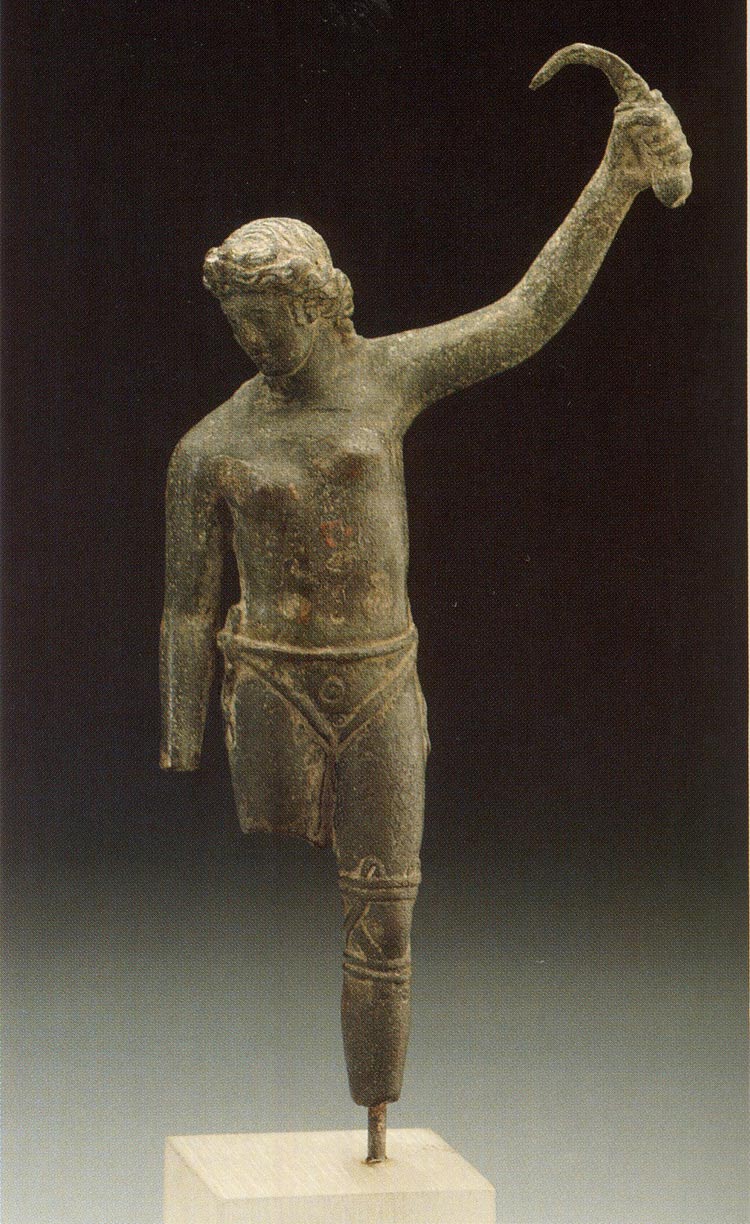

Sword of the Gladiatrix was inspired by a particular stone carving of two female gladiators in the British Museum. More recently, archaeologists have uncovered a bronze statue of a gladiatrix holding a sica—a curved sword. Tacitus, Suetonius, Dio, Martial, and Juvenal all write about female gladiators—usually (except for Martial) with some element of dismay or sarcasm. An organizer in Ostia brags on his tombstone that he was the first person to put women in the arena as fighters. My favorite evidence is in the law: The first Roman Emperor Augustus forbade recruiting noble and free women as gladiators. Nearly two hundred years later, Emperor Septimus Severus banned single combat by women in the arena. If women weren’t being recruited and fighting, why have a ban? Human nature being what it is, these prohibitions probably made the fights all the more popular because they were illegal. I’m sure female gladiatorial contests continued for some time.

Myth #2:

All gladiators were slaves or condemned criminals.

Freeborn people could contract with a ludus (gladiator school) for a set period of time (usually five years) in return for training and a signing bonus. Many did this to escape poverty and unemployment. Spartacus: War of the Damned has a free-born gladiator who joined to pay off his debts and care for his family. We have ample evidence of freeborn and noble men and women who freely took the oath to “be burned, bound, chained, beaten, or slain by the sword” that all gladiators swore. Most evidence comes from literature and law, as well as grave inscriptions and surviving lists of fighters which mention their status.

This was a significant step for a free person to take. They voluntarily gave up their protection under the law for the possibility of fame and fortune in the arena. Freeborn fighters were generally thought better than slave fighters because they chose to enter that life. Some gladiators who won or purchased their freedom signed up again, not wanting to give up the life they knew and were good at. We have no way of knowing the proportion of free vs. slave gladiators, but they did exist.

Myth #3:

Every gladiatorial contest ended in death.

This myth, perpetuated in the movies, is rooted in gladiatorial history. The first gladiator contests took place during public funerals for upper class people where pairs of slaves fought to the death as an honor for the deceased. The more dead slaves, the more “honor.” However, politicos quickly realized how these public funeral games pleased the crowds and started paying for gladiator match-ups at religious festivals and civic celebrations. At that point, the invisible hand of the market took over. Lanistae—gladiator providers—spent a lot of money procuring, training, and maintaining their stock. They didn’t want to lose 50% or more of their prized possessions at every game and the editors—those who gave the games—didn’t want to pay the price of dozens of dead and wounded gladiators. It was rare (except for emperors who could afford it) that an editor demanded a fight to the death, so the death rate for gladiator games was one in nine with most deaths occurring among the tirones—new recruits.

Top gladiators also inspired rabid fans who did not want to see their favorites killed. Early in Gladiator, Russell Crowe’s character (a former General named Maximus) is chastised for quickly and efficiently killing his opponent in the arena and depriving the audience of a show (no fancy twirling or leaping). The top gladiators entertained as well as fought (a little like wrestling today). They trained to show off their skills and fought only two or three times a year. Fans bought souvenirs with their likenesses and hired them to attend parties. Women paid to have sex with them and bought the sweat scraped off their bodies as an aphrodisiac. During an actual contest in the arena, most top fighters aimed to defeat their opponents without killing them. The defeated fighter could then appeal to the giver of the games for mercy and the editor could avoid paying a hefty fee for the dead fighter by granting it. Of course, if the crowd was unhappy with the performance and the editor needed the publicity, he could always swallow the loss and order the killing stroke.

Myth #4:

Gladiators had body builder physiques.

Other than Sumo wrestlers, have you ever seen a fat fighter in the movies or TV? Even if Kirk Douglas doesn’t live up to modern standards of hunkiness, he’s still athletic in Spartacus. Real gladiators? They packed on the pounds—particularly around the middle—to protect muscles, nerves, blood vessels, and vital organs. They could take shallow cuts (lots of blood, but no death) and survive—a crowd and owner pleaser.

Contemporaries called them hordearii—barley men—because of their plentiful but monotonous diet of barley and beans cooked together to make a thick soup or potage, probably seasoned with onions, leeks, and local herbs. They also bulked up on barley bread. The result of this diet of simple carbs is…fat.

Recent studies of bones from gladiator grave yards found another interesting physical fact: gladiators had much higher levels of bone calcium than in the general population, resulting in denser, heavier bones. This calcium boost probably came from a disgusting-sounding brew of charred wood or bone ash dissolved in vinegary wine which the ancient writers mention as a staple in the gladiator’s diet. I think I’ll stick to protein shakes.

Note: This article first appeared as a guest post at Let Them Read Books on July 8, 2015.

Copyright © Faith L. Justice, June 2015

Join my monthly newsletter and get a free eBook:

Great post! I didn’t know you have a new book out. I’ll go check it out. 🙂

Thanks, Nila! Hope you enjoy the book.

Interesting history! Like so many other masculinized elements of history.

Thanks for dropping by, Abigail!