Guest Post: Early-Modern Crime (and Punishment) in “The Raven’s Seal”

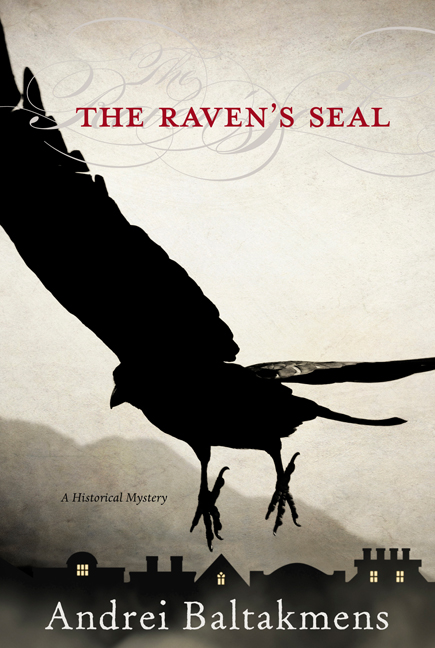

I’m back from New Zealand and–totally by coincidence–I’m hosting a New Zealand author. As readers of this blog know, I’m a Dickens fan. I can’t get enough of his quirky characters, dark settings, twisty plots and–yes!–even his social preaching. One of my favorites, Little Dorritt (reviewed here) features a debtor’s prison which is just as much a character as its human inhabitants. That’s why I was so pleased to score a copy of The Raven’s Seal a historical mystery written in the style of Dickens. The author Andrei Baltakmens is a Dickens scholar and plants an eighteenth-century prison in the heart of his novel. The gaol (jail for us in the US) broods over the prose and lurks in the background infusing the story with its dark presence. From the first paragraph:

I’m back from New Zealand and–totally by coincidence–I’m hosting a New Zealand author. As readers of this blog know, I’m a Dickens fan. I can’t get enough of his quirky characters, dark settings, twisty plots and–yes!–even his social preaching. One of my favorites, Little Dorritt (reviewed here) features a debtor’s prison which is just as much a character as its human inhabitants. That’s why I was so pleased to score a copy of The Raven’s Seal a historical mystery written in the style of Dickens. The author Andrei Baltakmens is a Dickens scholar and plants an eighteenth-century prison in the heart of his novel. The gaol (jail for us in the US) broods over the prose and lurks in the background infusing the story with its dark presence. From the first paragraph:

“The Old Bellstrom Gaol crouched above the fine city of Airenchester like a black spider on a heap of spoils. It presided over The Steps, a ramshackle pile of cramped yards and tenements teeming about rambling stairs, and glared across the River Pentlow towards Battens Hill, where the sombre courts and city halls stood. From Cracksheart Hill, the Bellstrom loomed on every prospect and was glimpsed at the end of every lane.”

Many thanks to Andrei for providing a guest post on eighteenth-century crime and punishment and to his publisher Top Five Books for providing a giveaway copy (details at the end of the post.)

Early-Modern Crime (and Punishment) in The Raven’s Seal

by Andrei Baltakmens

My novel, The Raven’s Seal, is a historical mystery set in and around a fictional eighteenth-century prison, the Bellstrom Gaol. The gaol is a commanding presence in the novel, presiding over the equally fictional city of Airenchester. But of course there would be no gaol, and no mystery, without crime and punishment, and though the Bellstrom dominated my imagination for a long time, the history of crime in the early-modern period (roughly 1500 to 1800), particularly under the Black Act, makes for a fascinating background which occasionally peeks through into the mystery.

My novel, The Raven’s Seal, is a historical mystery set in and around a fictional eighteenth-century prison, the Bellstrom Gaol. The gaol is a commanding presence in the novel, presiding over the equally fictional city of Airenchester. But of course there would be no gaol, and no mystery, without crime and punishment, and though the Bellstrom dominated my imagination for a long time, the history of crime in the early-modern period (roughly 1500 to 1800), particularly under the Black Act, makes for a fascinating background which occasionally peeks through into the mystery.

Although still mired in their medieval antecedents, the prisons of the eighteenth century multiplied rapidly as crime itself seemed to multiply. This was related to the Black Act, passed in 1723, which greatly expanded the scope of capital crimes in England to crimes against property. But this is only part of the story. Why did so many turn to crime in this period, and why did the penalties for crime expand so ferociously? This was a sign of broad and turbulent social changes: a growing population, industrialization, and a deep conflict between new capitalist practices and traditional concepts of tenure and property, between those who made fortunes and the many who lost what little they had. We saw, in this period, a growing tide of disenfranchisement, as enclosure converted common land to private ownership, often by dubious means, while at the same time the wealthy moved to protect their acquisitions with lethal penalties for small crimes. Social disruption and the loss of traditional livelihoods, the move to the cities, and the inadequacy of the Poor Laws all exacerbated the conditions for crime. It’s fascinating to an observer or writer that the penalties for breaking the law, so brutal to modern eyes, had little effect on this expansion in crime.

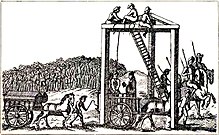

Prison itself was hardly regarded as a punishment (though the prisons were miserable, dangerous places); prison was simply a convenient place to hold felons before punishment, be that flogging, branding, hanging or transportation. Contemporary observers also recognized that gaols were by no means places where crime was curbed but rather colleges where criminality was nursed and encouraged. And the most gruesome punishment of all, hanging, was designed as a spectacle, a warning, an eighteenth-century equivalent of a public relations campaign. Many commentators, then and later, have noted that this campaign was a failure. Public hangings became grisly carnivals, as well as occasions for more crime, as pickpockets and others worked the crowds. Numerous victims of the gallows, from Dick Turpin to Jack Sheppard, became folk heroes rather than moral exemplars of a life gone bad.

Prison itself was hardly regarded as a punishment (though the prisons were miserable, dangerous places); prison was simply a convenient place to hold felons before punishment, be that flogging, branding, hanging or transportation. Contemporary observers also recognized that gaols were by no means places where crime was curbed but rather colleges where criminality was nursed and encouraged. And the most gruesome punishment of all, hanging, was designed as a spectacle, a warning, an eighteenth-century equivalent of a public relations campaign. Many commentators, then and later, have noted that this campaign was a failure. Public hangings became grisly carnivals, as well as occasions for more crime, as pickpockets and others worked the crowds. Numerous victims of the gallows, from Dick Turpin to Jack Sheppard, became folk heroes rather than moral exemplars of a life gone bad.

But all the more engaging for a writer of mysteries is the fluid relationship between the law and its erratic enforcement. The character of Brock, the thief-taker in my novel, is based on Mr. Peachum in Gray’s The Beggar’s Opera (to “peach,” by the way, is slang for impeach, or turn evidence against someone). Thief-takers, such as Jonathan Wild, were often corrupt, treating crime as a business, fencing stolen goods, dealing in protection, or returning goods they themselves had arranged the theft of, and deciding who would go before the magistrates. Before the development of police forces, the bailiffs, beadles, and watchmen had little power to enforce order. For a writer of mysteries, this opens up many rich possibilities.

Writing a mystery in this period, before any of the tools of policing or detection we are familiar with existed, offers a fine opportunity as well as challenges. Mystery plots are built around the how and why, but for me the fundamental question of mystery is: who is guilty? So many complex social forces collide at the nexus of crime and punishment in the eighteenth century that the answer to that question takes a whole book to expose, and yet leaves, I hope, many points to ponder.

About the Author

Andrei Baltakmens was born in Christchurch, New Zealand. He has a Ph.D. in English literature, focused on Charles Dickens and Victorian urban mysteries. His first novel, The Battleship Regal, was published in New Zealand in 1996. He has published short fiction in various literary journals, including a story in the collection of emerging New Zealand male writers, Boys’ Own Stories (2001). For five years he lived in Ithaca, New York, where he was part of the professional staff of Cornell University. He is currently a graduate student in the Creative Writing Program at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia, where he lives with his wife and son. You can contact Andrei through his blog “Displaced Pieces.”

Giveaway Details (US only):

Entry is easy: leave a comment on this post by midnight Sunday, December 9 (email not necessary in the comment, but please give it when asked, so I can get back to you if you win.) If you want a second entry, sign up to follow the blog or indicate you’re already a follower. For additional chances, repost this giveaway on your Facebook, blog, Twitter, website, etc. and post the link in your comment. Don’t worry if your post doesn’t appear immediately, because I moderate comments and don’t spend my life at my computer. I’ll randomly select the a winner and announce it on Monday, December 10. Good luck!

The Details:

- Title: The Raven’s Seal (416 pages)

- Author: Andrei Baltrakmens

- Publisher: Top Five Books

- Date: November 2012

- Trade Paperback ISBN/price: 978-0-9852787-5-5 ($14.00)

- eBook ISBN/price: 978-0-9852787-6-2 ($8.99)

Congratulations to our winner: windicindi!

I’ll be in touch by email to get your mailing address.

Oh oh oh, me me me! 😀

Great post, and the book sounds interesting. Always fascinating to see the development of modern societal norms – makes one appreciate our current (western) justice systems! Looking forward to reading it.

I’d love to join – please add me!

thank you for sharing this review.I recently posted an author interview and book review and wanted to look at other blogs on how they do it. I am new in book reviewing and thank you for posting something like this.

I am also following your blog now 🙂

Very interesting. I share your interest in the Dickens time. The Raven’s seal sounds like a great book and can not wait to read it!

I enjoy reading historical fiction very much; especially when

it revolves around suspense!

Many thanks, Cindi

jchoppes[at]hotmail[dot]com

I am an email subscriber to your blog…

Again, many thanks to you!

Cindi

jchoppes[at]hotmail[dot]com

“Tweet!”

https://twitter.com/cmh512/status/274915165013696512…

Merci, Cindi

jchoppes[at]hotmail[dot]com