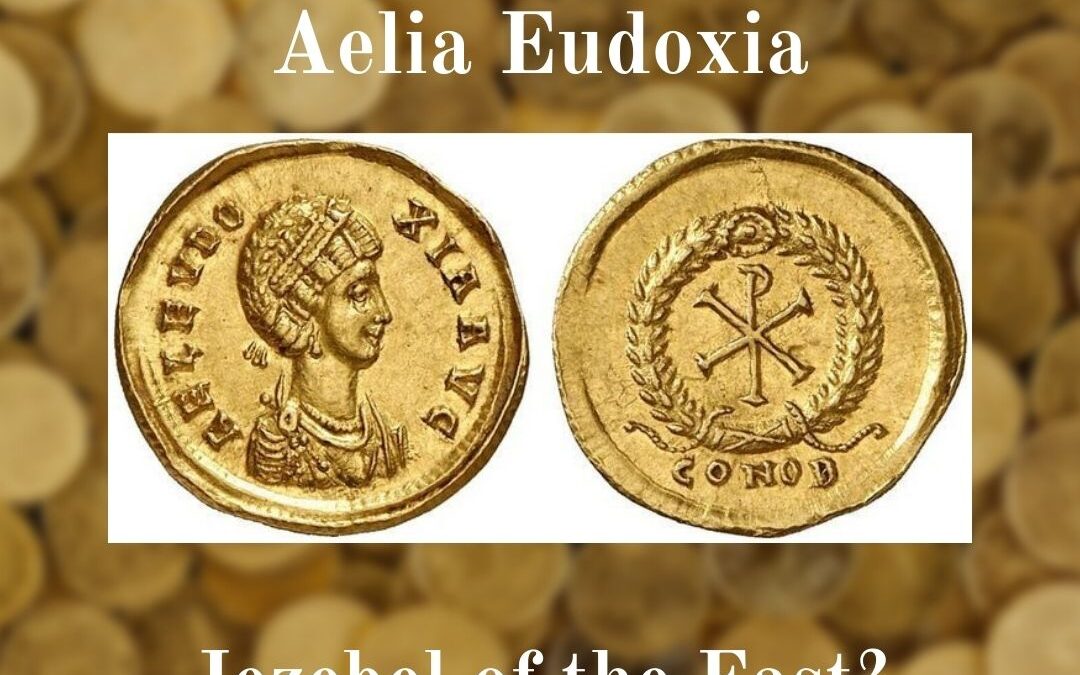

Empress Aelia Pulcheria

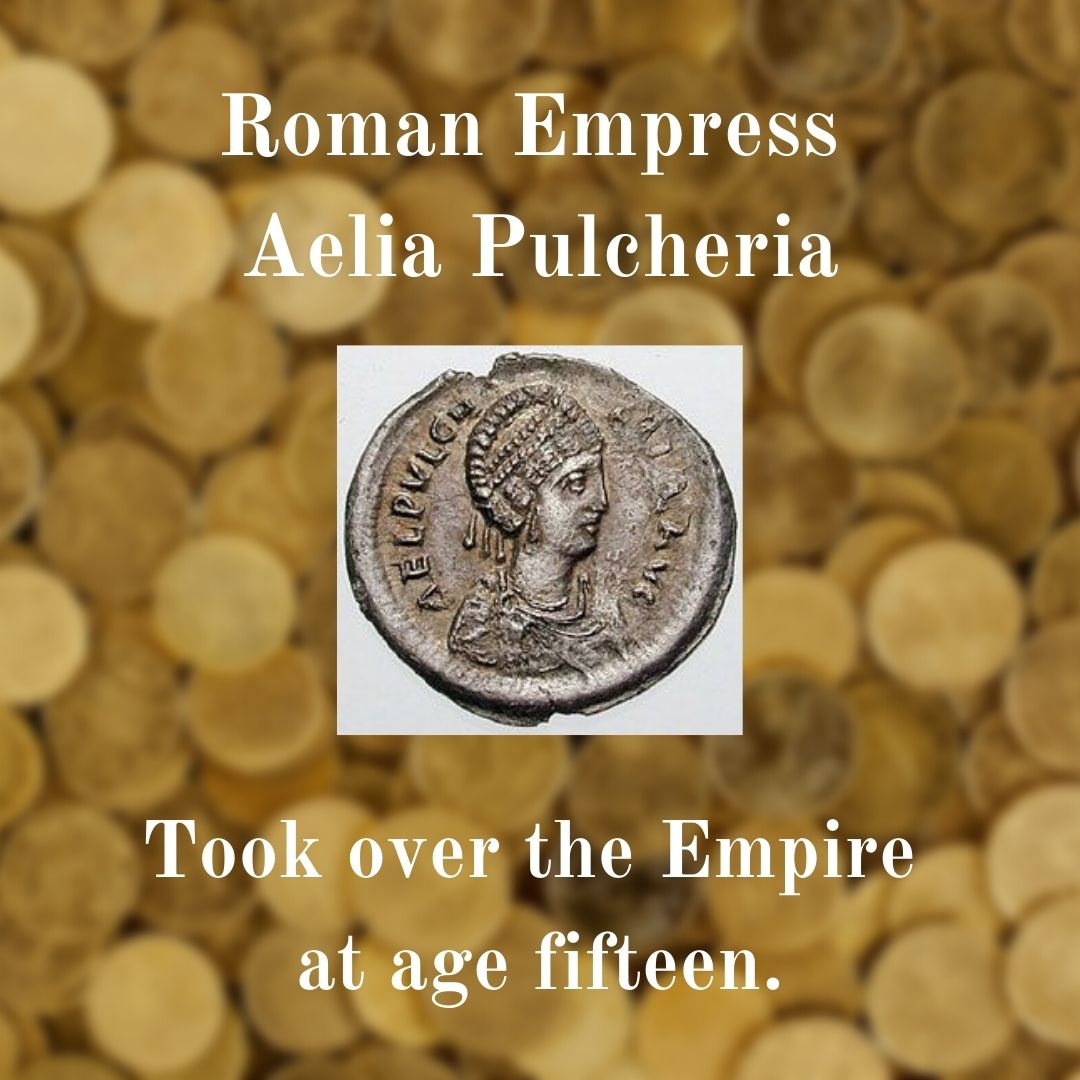

Roman Empress Aelia Pulcheria

Took over the Empire at age fifteen.

(b. 399, d. 453. Empress 414 – 453)

When I researched my first novel (Selene of Alexandria) about Hypatia the Lady Philosophy, I ran across Pulcheria, the fifteen year old girl who outwitted the men of the Eastern court to become Empress and regent for her underage brother Theodosius II. Her early reign coincided with my story and I used that in my plot. At the time I didn’t delve too deeply, but I made a note that I needed to learn more about this female prodigy. That’s how my infatuation with the Theodosian Women began.

Because Pulcheria is the protagonist of Dawn Empress, I won’t give too much away about her adult life and the plot of the story, but will give a sampling of her accomplishments—which were remarkable. Pulcheria represents in many ways the pinnacle of power that the Theodosian women attained. Daughter of the politically active Eudoxia and granddaughter of the saintly Flacilla, she emulated both and learned to wield power using the love of the people and the backing of the Church as her primary weapons. It’s what she used that power for that is the core of my novel.

As I mentioned in Eudoxia’s post, she had four children who survived in adulthood. Pulcheria, Arcadia, Theodosius, and Marina. They were orphaned young. Theodosius became emperor at age seven and Pulcheria was only nine. The boy emperor’s minority was a terribly fraught time. The Huns regularly raided the East. Persia, Rome’s traditional rival, threatened their borders.

In troubled times, ambitious men eye the throne occupied by a child and calculate their chances of successful regime change. An unscrupulous man or cabal of men might have arranged—with few consequences—any number of quiet ways to get rid of the child emperor, as has happened down through the centuries. (The Princes in the Tower, anyone?) I’m sure Pulcheria was acutely aware of these possibilities. Fear, insecurity, and lack of control probably dogged her childhood and shaped her actions into adulthood.

However, the imperial children lucked out when the Eastern Prefect Anthemius “the Great,” took over the government as regent and guardian. He saw that the children were well-cared for, educated, and prepared for their roles. Of course, he saw Pulcheria’s role as one of marriage—preferably into Anthemius’ family. Historians and the people of the time acclaimed him as a fair man who loved his city and administered the Eastern Empire well. Anthemius built the famous walls (that carried Theodosius’ name) around Constantinople that stood against enemies for a thousand years.

Even if she appreciated Anthemius’ fair dealing, Pulcheria likely felt that the only person who could adequately protect her brother and his rule, was herself. She certainly didn’t want to be sidelined with a marriage in which a mature husband might prove a threat to her young brother. Given her mother Eudoxia’s fate, she probably didn’t want children which might be a threat to her own life.

With her brother’s consent and the help of the Church, Pulcheria and her sisters took vows of chastity and dedicated their virginity to their brother’s rule. They lived as holy women, but not under any churchman’s rule, neatly maintaining their freedom from noble men and the Church. When she came of age at fifteen, Theodosius declared Pulcheria Empress, regent, and chief councilor. She took over the government and only let go when she was on the outs with her brother—which happened a couple of times over his long reign.

Pulcheria felt Theodosius was particularly susceptible to undue influence and was constantly on guard against it, causing most of the conflict between her beloved brother and herself. Some might even argue that Pulcheria WAS a threat to her brother, stifling his abilities and usurping his authority, but I doubt that she would agree. She was fierce and determined in her love for her brother, the people of Constantinople, and the orthodox Church which made her a saint. Her feast day is September 10.

As a side note, the imperial princesses Arcadia and Marina are technically Theodosian Women, but they were so overshadowed by their older sister, that they left no legacy other than their devotion to her and their brother. In my novel, I gave them a little more agency and personality, but it’s all fiction. They sadly left no clues in history to tell their own stories.

Next up is Empress Aelia Eudocia, known as Athenais before she converted to Christianity and married Theodosius II.

Join my monthy newsletter below and get a free eBook set in the Thodosian Women series.

Image of Pulcheria on a coin licensed through Creative Common by Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4995486