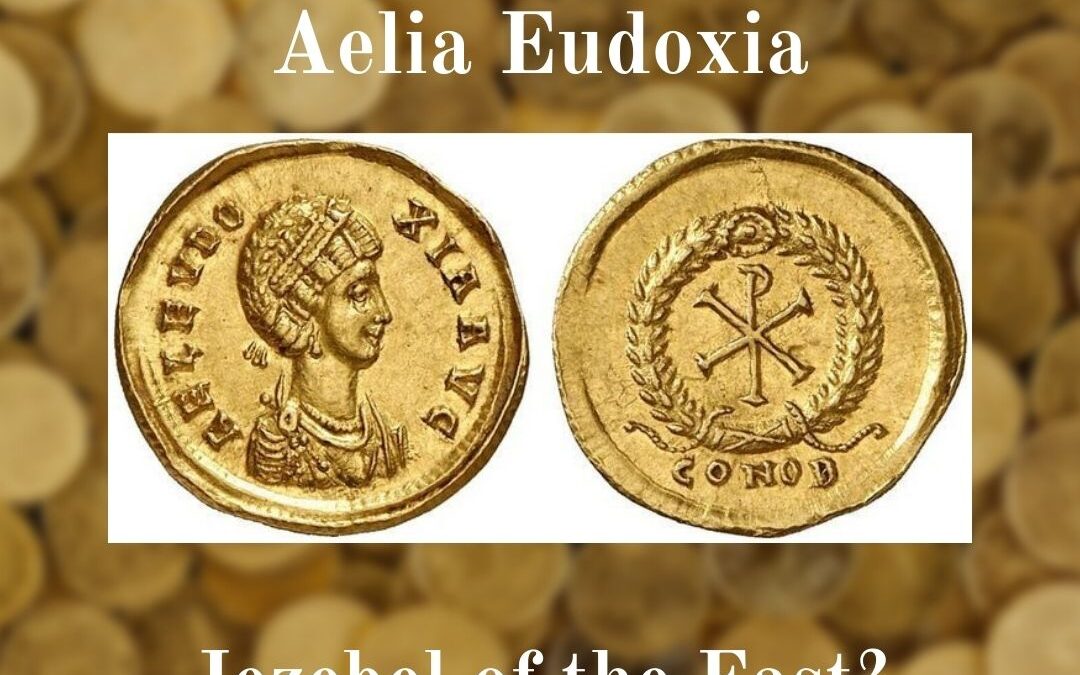

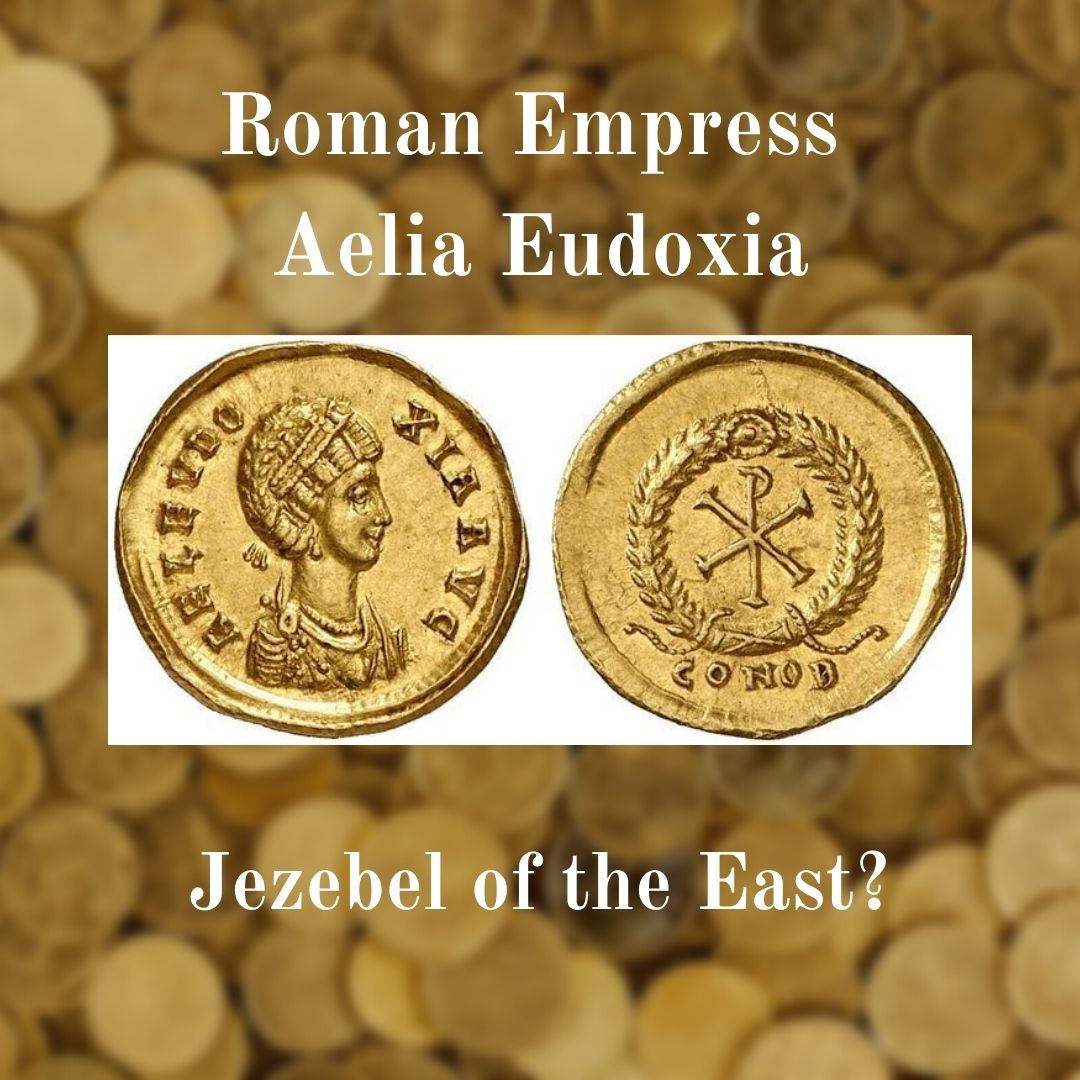

Empress Aelia Eudoxia

Roman Empress Aelia Eudoxia

Jezebel of the East?

(b.?, d. 404, Empress 395-404)

Was she or wasn’t she? It depends on whether you’re a modern historian who admires assertive women or a fifth century bishop. Eudoxia was the attractive daughter of a Romanized Frankish General and—initially—a pawn in a palace intrigue. After Theodosius’ death in early 395, his oldest son Arcadius became co-Emperor in Constantinople. The nobles and palace eunuchs schemed for control of the “lethargic” emperor. The eastern Prefect had a marriageable daughter, but the chief eunuch of the imperial household got there first. Before Theodosius’ body could arrive in Constantinople for burial, the eunuch’s choice, Eudoxia, married the new emperor while the prefect was out of town.

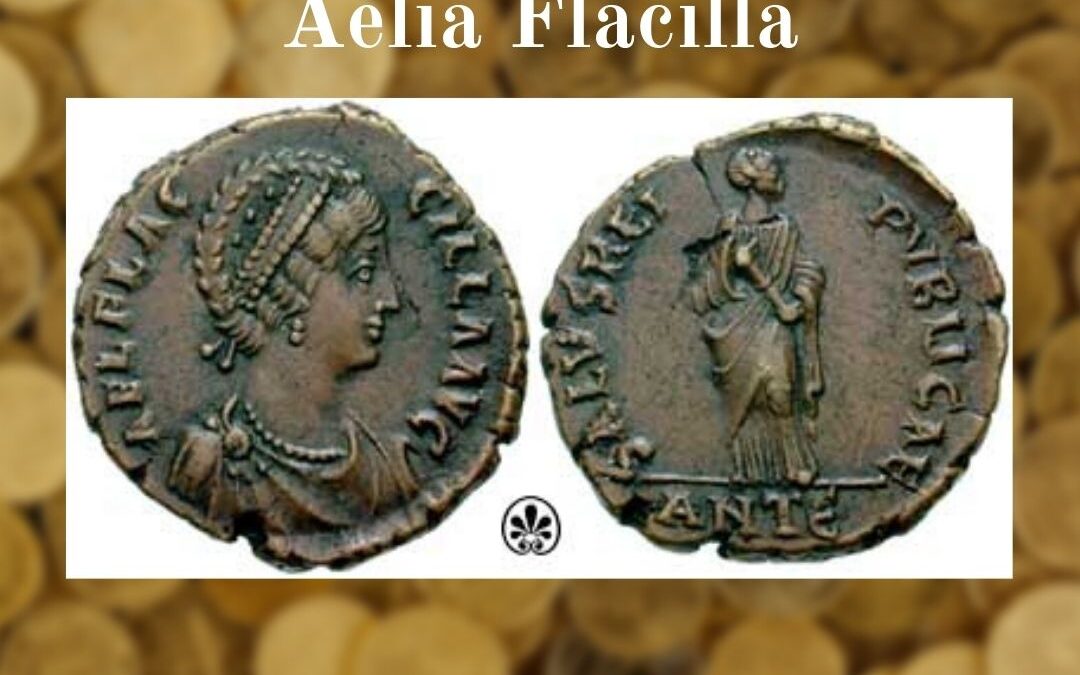

Once in power, Eudoxia proved she was no longer a pawn. She modeled herself on her dead mother-in-law, the sainted Flacilla, taking her nomen Aelia, and proving her fertility by having five living children. After three daughters, she finally gave birth to a male heir Theodosius II. Her oldest daughter Flacilla died young, but Pulcheria, Arcadia, and Marina (youngest child born after Theodosius) lived well into adulthood and I chronicle their stories in Dawn Empress: A Novel of Imperial Rome.

Also like her predecessor, she turned her eyes to the Church to enhance the imperial reign. Eudoxia lavished money on silver candle sticks and acquired saints’ relics to adorn the churches, but she went a step beyond Flacilla. Instead of serving the poor and destitute, Eudoxia engaged in politics directly affecting Church doctrine. When Arcadius’ advisors refused a petition from prominent Churchmen to demolish a pagan temple in Gaza, she arranged for her infant son to grant the request. She ordered her agent to “demolish to their foundations all temples of idols.”

In spite of these and other “good deeds” she ran afoul of the Bishop of Constantinople who considered her arrogant and greedy. And the nobles she bested didn’t like having an uppity woman in control of the emperor either. They openly gossiped about the parentage of the young heir, and named a favorite courtier of Eudoxia’s, Count John, as the true baby-daddy. That gossip still shows up in the history books, but without a paternity test, we can’t know the truth.

Bishop Chrysostom denounced the empress as a modern Jezebel, the embodiment of queenly evil, but he didn’t like women much. He preached against women taking on any role other than one of subservience. When the city prefect erected a silver statue of Eudoxia before the senate house, Chrysostom thundered another sermon, this time comparing the empress to Herodias who aimed “to have the head of John on a platter.” Eudoxia had him banished.

Unfortunately, Eudoxia didn’t have long to relish her victory. She died of a miscarriage on October 6, 404, but left a potent legacy for her daughter Pulcheria, when she came to power.

Coming up next: Empress Galla Placidia, the Twilight Empress, daughter of Theodosius.

Sign up for my monthly newsletter below and get a free eBook set in the Theodosian Women series.

Coin image available through Creative Commons, licensed By Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=47717643